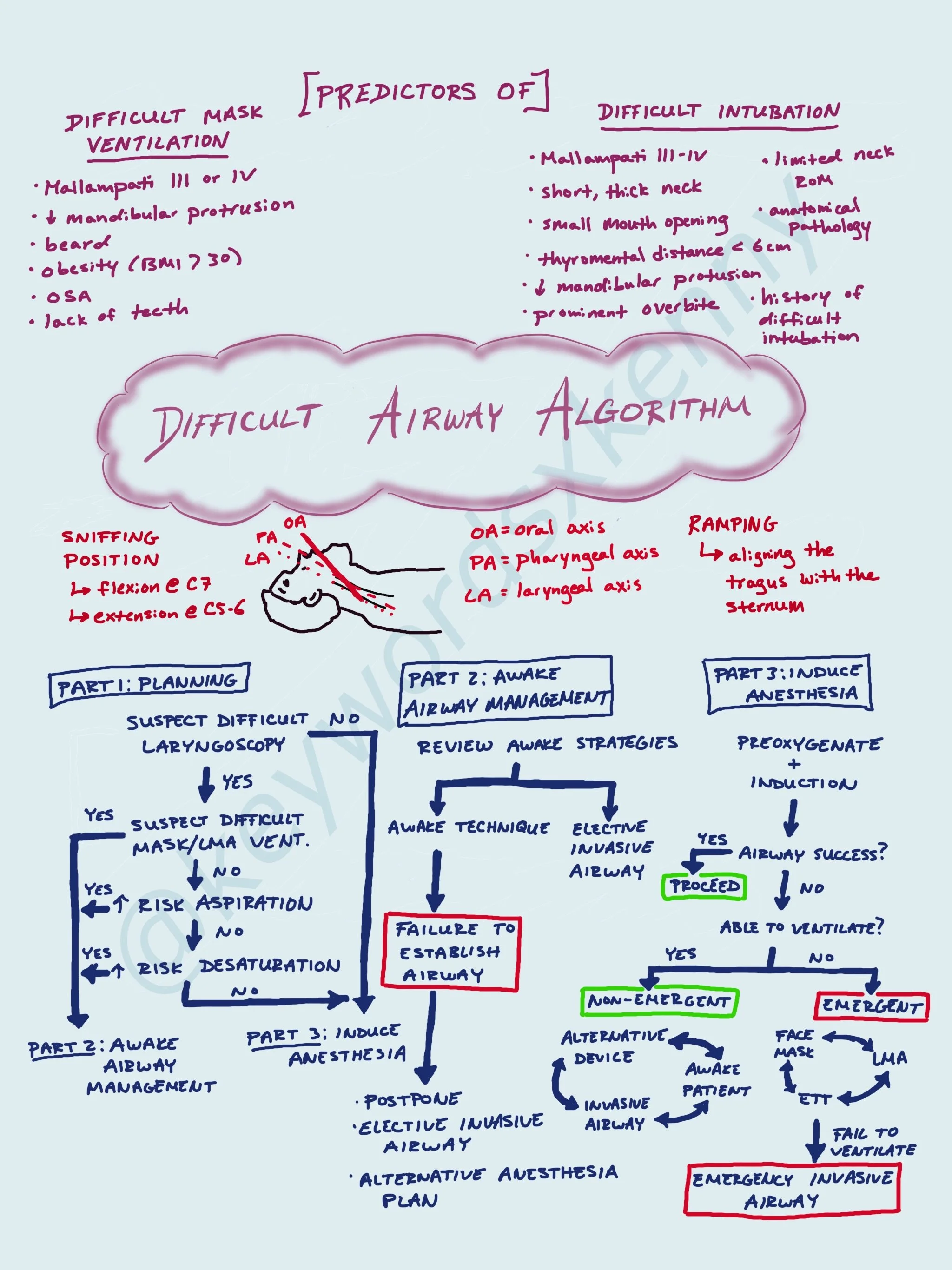

Difficult Airway Algorithm

One of our most vital jobs as Anesthesiologists is managing the airway. We are considered “airway experts” in the medical field. When you first start off as an anesthesia resident, majority of intubations seem difficult. Overtime you develop the dexterity and familiarity with airway anatomy to be able to intubate almost everyone. However, there are still patients you will encounter who will have a difficult airway. Without adequate ventilation and oxygenation after induction of anesthesia, your patients may deteriorate very quickly. Therefore, you must be prepared with an airway plans prior to putting the patient to sleep! The American Society of Anesthesiologists have developed guidelines to help physicians manage difficult airway scenarios. These scenarios can be stressful with very little time to fumble - knowing the key points of the guidelines will save you from being in a dire situation.

Let’s start with some definitions from the ASA. A difficult face mask ventilation is the inability to provide adequate ventilation because of either inadequate mask seal, excess gas leak, or excessive resistance to the ingress or egress of gas. Difficult laryngoscopy refers to the inability to visualize any portion of the vocal cords after multiple attempts at laryngoscopy. Signs of poor or inadequate ventilation include absence of exhaled carbon dioxide (ie. end-tidal CO2), absent/diminished breath sounds, absent chest movement, auditory signs of severe obstruction, cyanosis, gastric distention, and hypercarbia/hypoxia. Bad outcomes associated with a difficult airway can include death, brain injury, cardiac arrest, airway trauma, damage to teeth.

The goals of these guidelines are to guide management of patients with difficult airways, optimize first attempt success, improve patients safety during airway management, and avoid/minimize adverse events. First we will discuss the airway exam.

A full airway examination includes risk assessment for factors that would lead to a difficult airway or risk of aspiration and a visualization of airway anatomy (ie. at bedside and/or on imaging). The physical exam includes assessments of facial features and anatomical measurements and landmarks. There are different factors that are predictive for a difficult mask seal vs. difficult intubation (although some overlap).

Predictors of a patient who would be difficult to mask ventilate include:

Mallampati III or IV

Decreased mandibular protrusion

Beard

Obesity (BMI > 30)

OSA

Lack of teeth

Predictors of a patient who would be difficult to perform laryngoscopy on include:

Mallampati III or IV

Short, thick neck (> 40 cm)

Small mouth opening

Thyromental distance < 6 cm

Decreased mandibular protrusion

Prominent overbite

Limited neck range of motion

Anatomical pathology (ie. tracheal stenosis, oropharyngeal tumor)

History of a difficult intubation

If your examination leads you to believing your patient is going to have a difficult airway, there are a few things to have prepared. Ensure that a skilled person with airway management experience is present (ie. Anesthesiologist). Inform the patient of special risks associated with advanced airway techniques. Properly position the patient and administer supplemental oxygen as long as possible prior to airway manipulation. Use ASA standard monitors before, during, and after securing the airway.

In terms of your airway plan, that will be determined by the type of surgery, health status of the patient, age, patient cooperation, and skills of the provider. There are 4 pathways you can find yourself in:

Awake intubation

Patient who can be ventilated but difficult to intubate

Patient who can not be ventilated or intubated

Difficulty with emergency invasive airway rescue

You will likely develop your preferred technique for awake intubations overtime and by trying different ways to sedate your patient and anesthetize the airway. The scariest moments are when you find yourself in an unanticipated and emergency difficult airway after the induction of anesthesia. As soon as you encounter this scenario, immediately call for help and optimize oxygenation. If you are having difficulty with laryngoscopy, remember to be cautious of the time you take and number of attempts to decrease desaturation time and potential injury to the airway. Having a different blade or using video-laryngoscopy can be helpful. Consider having a different provider attempt after initial provider attempts twice. If you are unable to mask ventilate with an oral airway in place, your next move will be to place a laryngeal mask away (LMA). You can intubate through an LMA using a fiberoptic camera as well. If you are unable to ventilate with an LMA, you should consider emergency invasive airway rescue procedures such as a cricothyrotomy. ECMO can be an ultimate last option if and when available.