Regional Anesthesia

As Anesthesiologists, post-operative pain control is a high priority for our peri-operative goals. Many patients are rightfully anxious about the pain they will be in after surgery. It is our job to create the best treatment plan curated for the specific patient and procedure involved. Over the past decade, we have incorporated a multi-modal approach to treating pain. This involves using a variety of medications that attack different receptors and act synergistically to reduce the overall dose needed to treat the pain and reduce the side effects that come with higher doses. Regional anesthesia refers to procedures that Anesthesiologists can perform that will help block pain to certain parts of the body. These techniques can help reduce the overall narcotics needed to treat a patient’s pain and allow a patient to get back to their daily activities sooner.

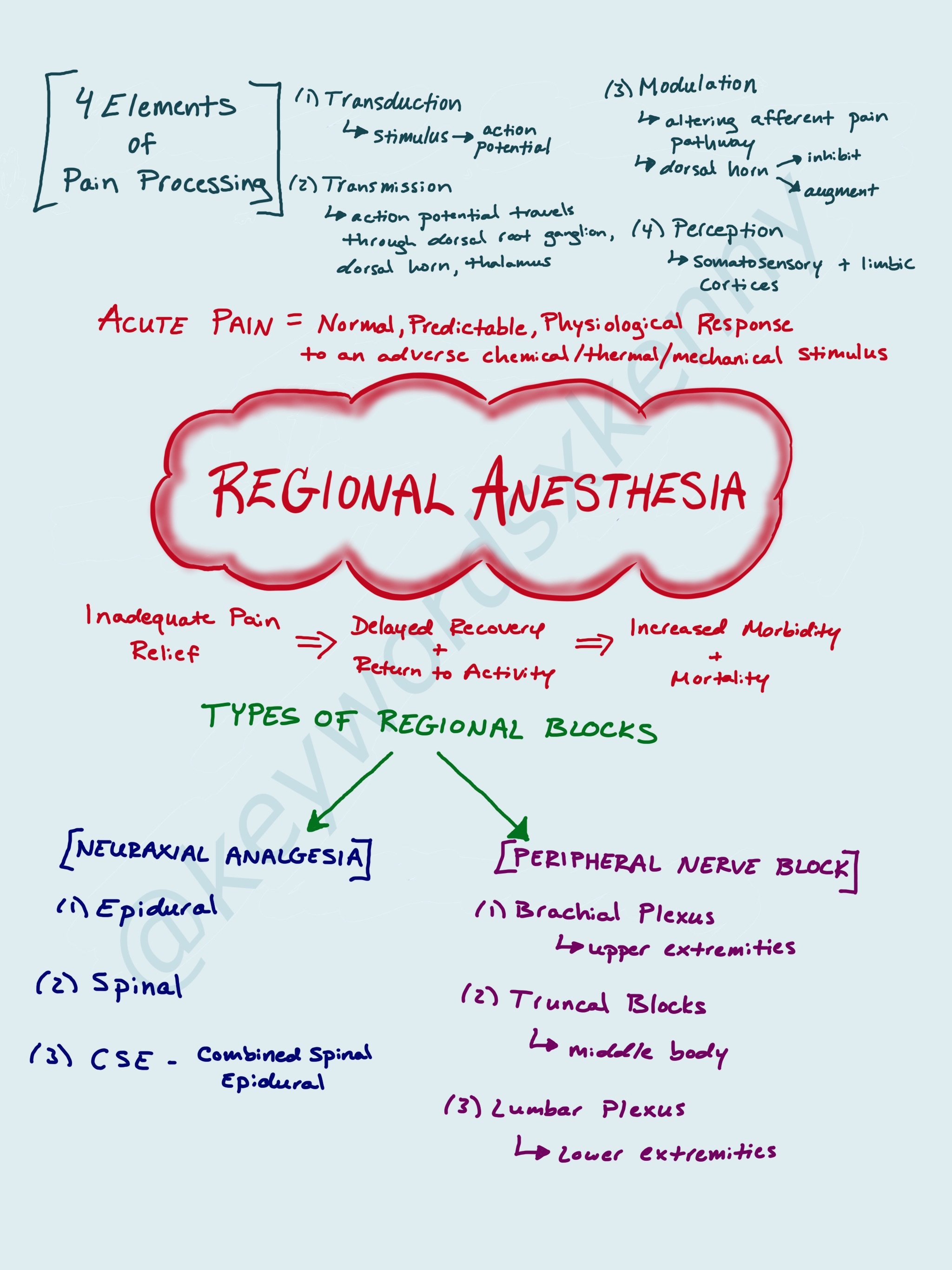

Let’s start with some common definitions:

Pain (nociception): an unpleasant sensory and emotional experience caused by actual or potential tissue damage

Acute Pain: follows injury to the body and generally disappears when the injury heals. This is the time needed to reduce inflammation and for incisions and lacerations to repair. Commonly lasts around 7 days but can persist up to 30 days.

Chronic (persistent) Pain: pain that persists beyond the time of healing. It is typically considered chronic if it lasts longer than 3 months.

Pain can be very debilitating for patients after surgery. For example, after open abdominal surgeries, patients may not be able to take deep breaths, stopping early in inspiration due to pain. This leads to atelectasis and potentially a pneumonia. There are certain factors that make a patient high risk for post-operative pain. These would include preoperative opioid use, increased BMI, anxiety, depression, fibromyalgia, and duration of surgical operation. A particular population to be cautious with is the elderly as pain medicine like narcotics can lead to delirium and prolonged hospital stays.

If acute pain is not adequately treated, this can lead to the development of chronic post surgical pain. This is largely unrecognized and can be as prevalent as 10-65% of post-op patient. This is most common after limp amputation (30-83%), thoracotomy (22-67%), sternotomy (27%), breast surgery (11-57%), and open abdominal surgery (up to 56%).

The acute pain service is a common division within a Department of Anesthsiology. They consist of a team of specialized members who are able to provide services to patients who are about to have surgery, undergoing surgery, or are recovering from surgery. Their goal is to reduce the pain resulting from surgery and minimize the time it takes to recover and decrease the likelihood of developing chronic post surgical pain.

Regional Anesthesia procedure fall into two broad categories: neuraxial analgesia and peripheral nerve blocks.

Neuraxial analgesia refers to intrathecal (spinal) and epidural administration of local anesthetics plus or minus opiates to achieve analgesia. These techniques have shown to decrease morbidity and mortality in certain surgeries. Intrathecal administration, or spinal analgesia, is a one-time injection near the dermatomal site of where you want to block pain. Depending on which local anesthetic you use, you will have a sensory and motor blockade that will last about 3 to 6 hours. Intrathecal opioids can be added for additional analgesia. Their duration of action is affected by their lipophilicity. Lipophilic drugs like fentanyl are short acting and get quickly absorbed out of the intrathecal space. The biggest disadvantage is the lack of flexibility with only a one short injection. Once your spinal wears off, you need to either use a different method of analgesia or perform an additional spinal injection. Epidurals are continuous infusions of local anesthetics plus or minus an opioids through a catheter that sits in the epidural space. Adding opioids to the epidural infusion helps ensure adequate analgesia without significant hypotension and motor blockade. For abdominal surgeries, epidural analgesia has proven to be superior to systemic opioid administration for postoperative pain control. Thoracic epidurals are quite common for thoracotomies and rib fractures. The biggest consideration to make when deciding on neuraxial anesthesia is the patients anticoagulation status. It is important to know if your patient is on anticoagulation medicine or has an underlying coagulopathy to avoid a spinal hematoma when performing both a spinal and epidural.

Peripheral nerve blocks are a great adjunct for multimodal pain relief when used appropriately. Nerve blocks used to be done using anatomical landmarks and nerve stimulators to let you know when your needle was close to the perineural space. However, current practice is to your ultrasound guidance in real time to identify your targeted anatomy and visualize your local anesthetic dispersing around the perineural area. Adjuvant drugs like dexamethasone and dexmedetomidine can be added to the local anesthetic to increase the duration of the nerve block to upwards of 3 days. Providers can also place catheters nerve the targeted nerve to allow a slow infusion of medication that will provide analgesia for multiple days. Upper extremity surgeries such as shoulder surgery are amenable to brachial plexus blocks. Lower extremity surgeries like knee replacements are good candidates for lumbar plexus blocks. Truncal blocks (ie. paravertebral, TAP block, PECS block) are usually for surgeries involving the upper body such as breast surgery or open abominable surgeries.