The Brachial Plexus

This will provide an overview of the brachial plexus - it’s specific anatomy and how we can utilize various segments of the plexus to provide analgesia to specific areas in the upper extremity.

Regional anesthesia is an effective way to provide analgesia to a patient by “blocking” nerves to an area of the body undergoing surgery with local anesthetics. The brachial plexus is particularly useful for blocking nerves that supply the upper extremity.

Nerve blocks can be a useful method of anesthesia for patients with specific medical comorbidities or anatomical variations that make general anesthesia higher risk. For example, patients with severe COPD or cystic fibrosis or cardiac dysfunction such as severe aortic stenosis or severe pulmonary hypertension would highly benefit from a peripheral nerve block with minimal sedation during the operation.

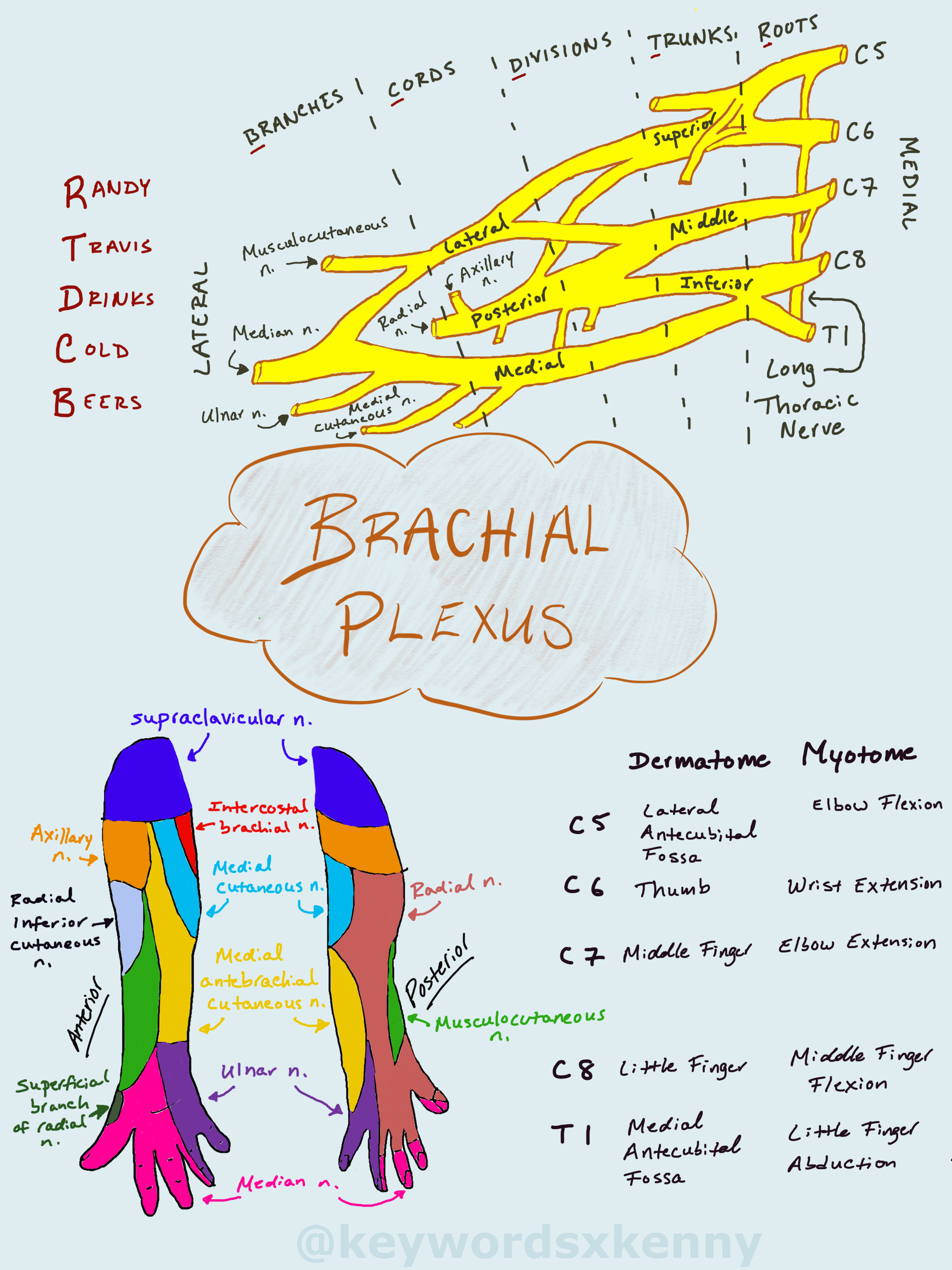

The brachial plexus is formed from the C5 to T1 nerve roots. These nerve roots combine to form the superior, middle, and inferior trunks above the clavicle. As they pass under the clavicle, the nerves come close in proximity to create the divisions. Past the clavicle, the divisions break into the medial, lateral, and posterior cord. Finally, the terminal nerve branches are formed in the axilla.

Based on this progression of nerve anatomy, the brachial plexus can be blocked at 4 different spots - each with their own indications based on the site of surgery and their own side effects/complications. They are named by their anatomical locations: (1) interscalene, (2) supraclavicular, (3) infraclavicular, and (4) axillary blocks.

Based on this progression of nerve anatomy, the brachial plexus can be blocked at 4 different spots - each with their own indications based on the site of surgery and their own side effects/complications. They are named by their anatomical locations: (1) interscalene, (2) supraclavicular, (3) infraclavicular, and (4) axillary blocks.

The equipment needed for these blocks include:

high frequency (> 10 MHz) linear ultrasound probe

Chlorhexidine 2% or povidone-iodine skin disinfectant

Local anesthetic (20-30mL bupivacaine 0.5% or Ropivacaine 0.5%)

Short bevel block needle (50-100mm, 21-22G), extension tubing

Sterile ultrasound probe cover with ultrasound gel

Standard vitals monitoring: NIBP, pulse oximetry, ECG

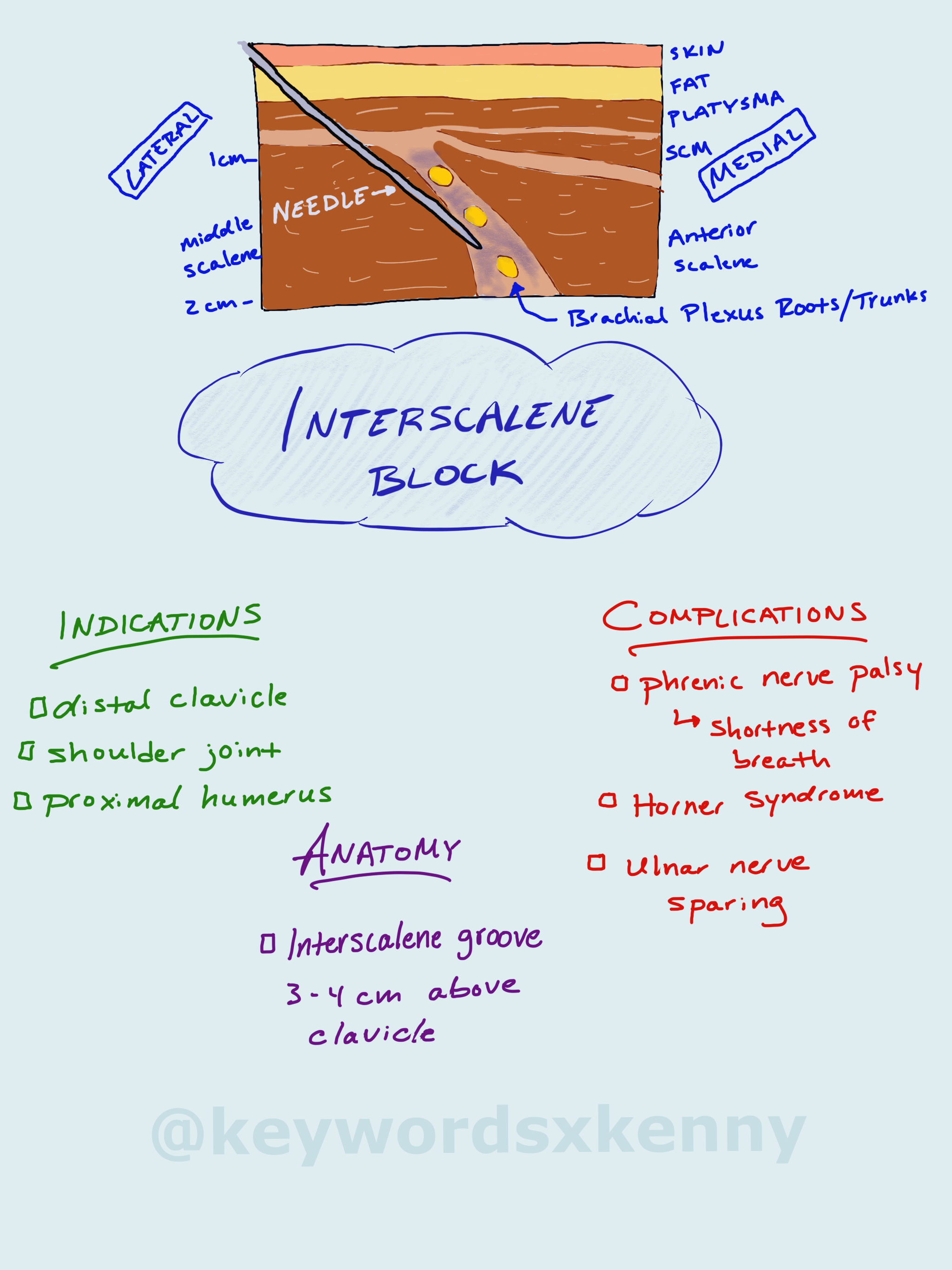

Interscalene blocks will provide analgesia and surgical anesthesia from the distal clavicle to the proximal humerus. It is commonly used for shoulder surgery.

When performing the interscalene block, have the patient supine with the head of the bed slightly elevated and their head facing away from you. Most providers will first find the supraclavicular view, visualizing the brachial plexus next to the subclavian artery. Next, you can trace the brachial plexus cephalad until you find the “stoplight” appearance of the roots/trunks between the anterior and medial scalene muscles. Your needle will enter from lateral to medial in the interscalene groove, in-line with the ultrasound probe. Ultimately you will deposit local anesthetic between the two scalene muscles, surrounds the trunks of the brachial plexus.

At this level of the brachial plexus, the inferior trunk (C8-T1) is often missed, sparing the ulnar nerve. This makes this block less suitable for surgeries involving the forearm and wrist.

The phrenic nerve is unintentionally blocked almost 100% of the time with an interscalene block. This causes hemidiaphragm paralysis and shortness of breath. You most likely would not perform this block on a patient with significant pulmonary disease like COPD or interstitial lung disease. It is also common to see Horner’s syndrome (miosis, ptosis, anhidrosis) due to the close proximity of the stellate ganglion in the neck.

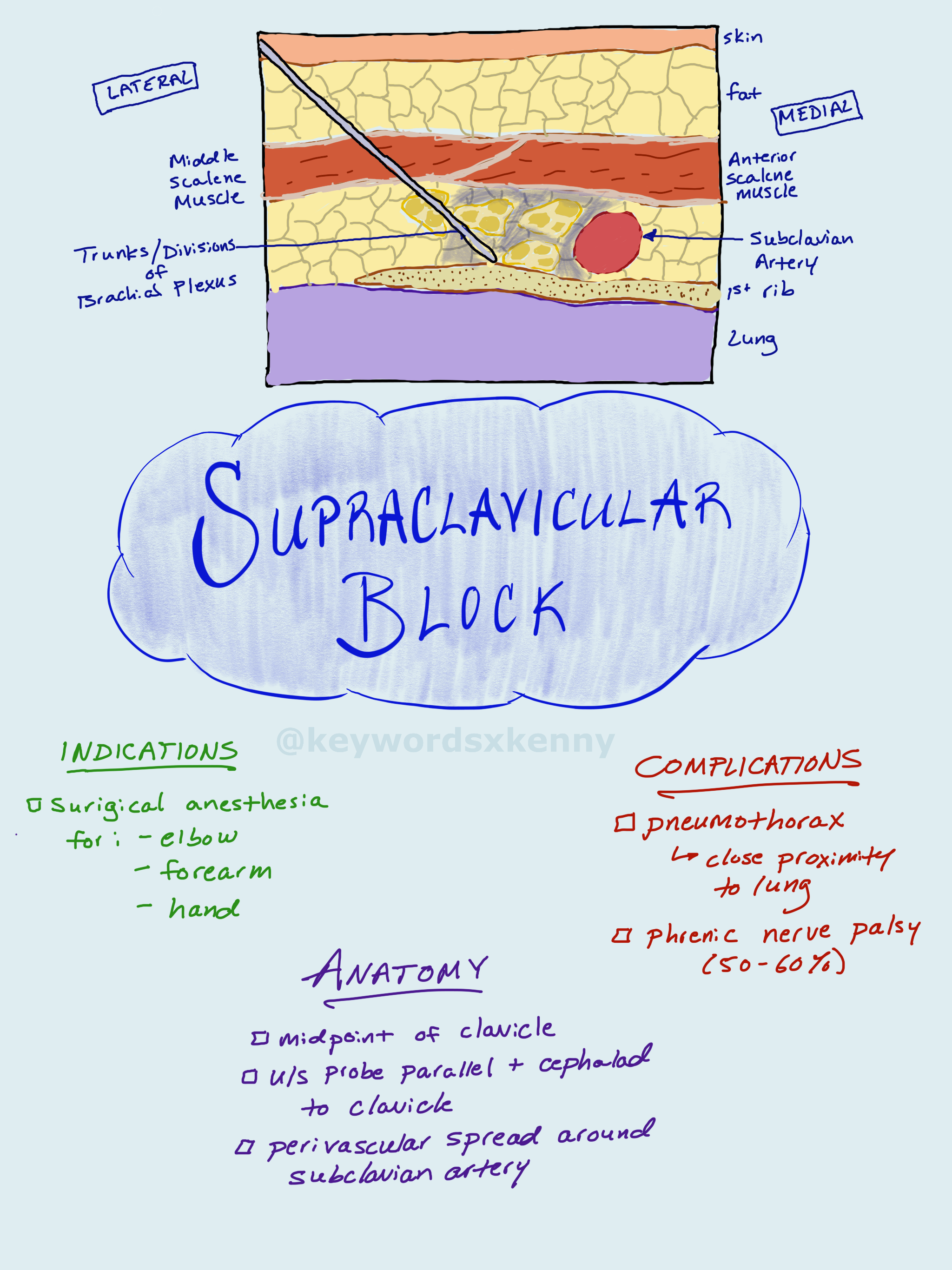

The supraclavicular block provides excellent surgical anesthesia for surgeries involving the elbow, forearm, and hand. The close proximity of the trunks and division at the levels of the first rib allows for small volumes of local anesthetics to provide rapid and profound neural blockade.

Your patient will be in the supine position with the head of the bed slightly elevated and the patient’s head facing away from the operative side. Having the patient reach down towards their knee on the side of the nerve block can help open up the clavicular space. Using the ultrasound, you will place your probe parallel and cephalad to the clavicle at its midpoint. After you identify the subclavian artery, you will see the brachial plexus nerve bundles surrounding the lateral side of the artery. If you can find the first rib, this can act as a backstop for your needle to prevent a pneumothorax. Next, insert your needle inline with the ultrasound probe and advance it until the tip is within the nerve sheath of the brachial plexus. As you inject local anesthetic, you will see the subclavian artery displaced medially.

The major complication associated with the supraclavicular block is a pneumothorax, given the close proximity to the lung. The incidence ranges from 0.5 to 6%. A phrenic nerve palsy occurs in about half of patients - significantly less than patient who receive an interscalene block (95-100%). Less commonly, you can see blockade of the recurrent laryngeal nerve (voice hoarseness), and cervical sympathetic nerves (Horner’s syndrome). Nerve damage is usually very rare and transient. Most nerve ischemia occurs from high pressure injections which can be prevented by performing nerve blocks on sedated but awake patients who can give you feedback if an injection is feeling too painful.

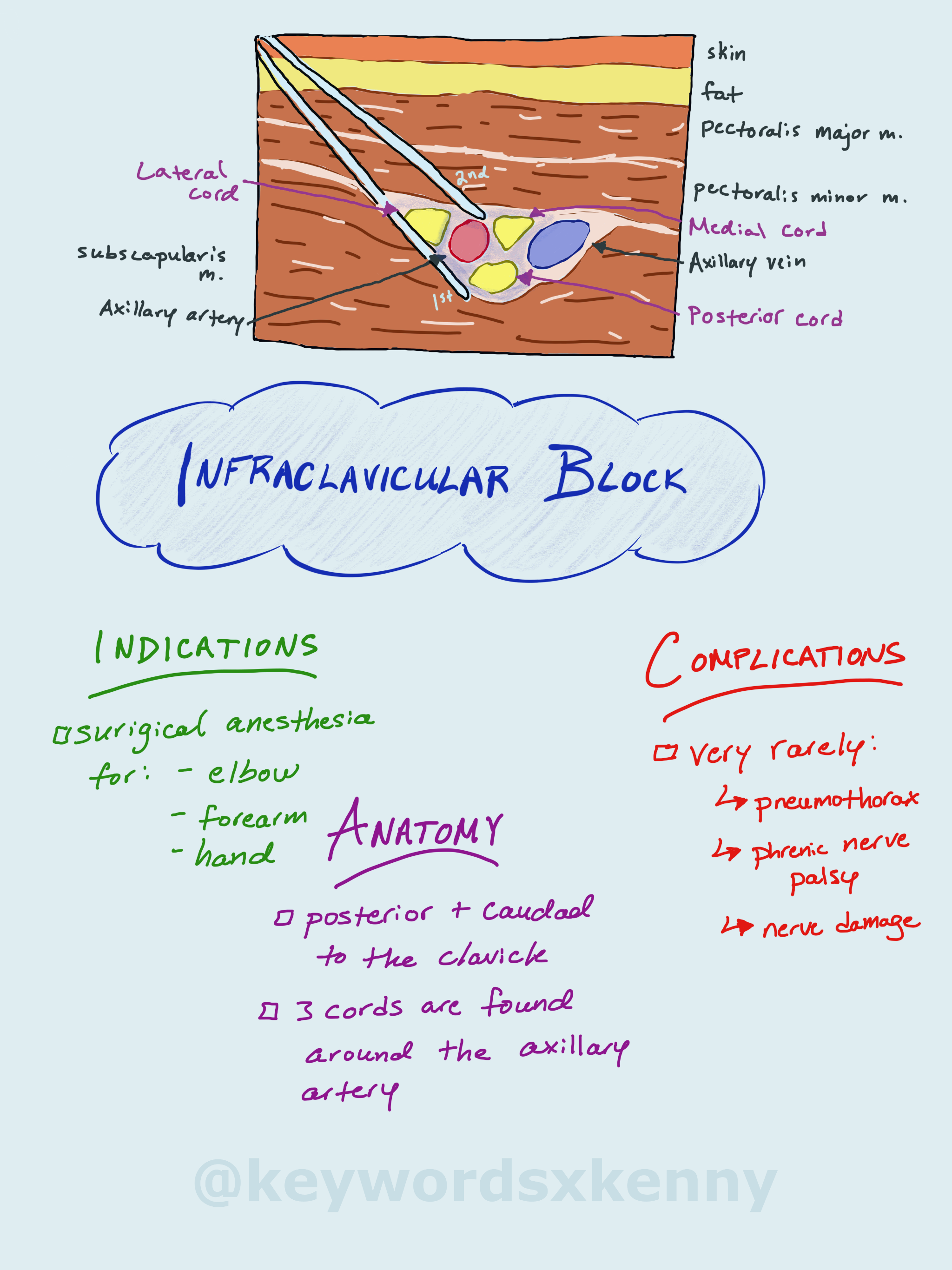

The infraclavicular block, as the name implies, occurs below the clavicle, at the level of the cords in the brachial plexus. The structure here can dive deep under thick muscle and fat layers that can make this block technically challenging. One way to bring the structures closer to the surface is to have the patient abduct their arm as much as possible (up to 90 degrees at the shoulder with the elbow flexed). The thick muscles do have one advantage in that this would be a great place to leave a catheter for a continuous infusion as the musculature of the chest anchors in the catheter.

Your patient will be in the supine position. The ultrasound probe is placed perpendicular to the lateral aspect of the clavicle towards the axilla. The more lateral you stay, the further from the lung pleura you will be, decreasing the risk of a pneumothorax.

Around the axillary artery, you can see the 3 brachial plexus cords, named for their relationship around the axillary artery: medial, lateral, and posterior cord. You can reliable block the plexus at this level by observing local anesthetic deposited in a “U-shape” around the artery.

If you are using nerve stimulation (0.5-0.8 mA, 0.1 msec), the first motor response you will see is from the lateral cord (elbow or finger flexion), followed by motor response from the posterior cord (wrist and finger extension).

This block will provide surgical anesthesia to the upper extremities below the shoulder. If the skin of the medial aspect of the upper arm needs to be covered for a tourniquet, you should additionally block the intercostobrahcial nerve (T2) by injecting subcutaneous LA to the medial aspect of the arm just distal to the axilla.

Complications with this block are very rare. Occasionally you can have sparing of the medial cord as this lies on the opposite site of the axillary artery from your needle insertion. Very rarely will you see injury to the lateral and posterior cord or axillary artery/vein. If the provider aspirates back on the syringe after every 3-5 ml of LA injected, it is very rare to have intravascular injection.

The axillary block is the most distal block of the brachial plexus. You do not block the axillary nerve as this takes off more proximally in the axilla from the posterior cord. It is useful for elbow, forearm, and hand surgery. At this point in the brachial plexus, you can block the musculocutaneous, median, ulnar, and radial nerve individually as they branch off from the cords.

It is considered a relatively simple block to perform with very low risk of complications when compared to the interscalene and supraclavicular nerve blocks.

Again, you will have your patient position supine in a stretcher with their arm abducted out 90 degrees. Using the medial aspect of the upper arm, the ultrasound probe will be placed sagittal or perpendicular to the axis of the arm. As you slide the transducer proximally, you will begin to see the axillary artery and the surrounds nerves.

These structures are usually quite superficial (1-3 cm below the skin). Around the axillary artery, you will see 3 of the 4 branches of the plexus. The median nerve is found superficial and lateral to the artery. The ulnar nerve is found superficial and medial to the artery. And the radial nerve is found posterior and lateral or medial to the artery. These structures are typically hyperechoic on ultrasound. The musculocutenous nerve is located in the fascial layer between the biceps and coracobrachialis muscle. There is a fair amount of anatomically variation from patient to patient.

The goal is to deposit local anesthetic all around the axillary artery and the musculocutaneous nerve. This typically requires 2 to 3 redirections of your needle to get to the right spots. A total of 20ml of local anesthetic is usually sufficient for this block.