Spinals and Epidurals

This is a review of the anatomy, dosing, and complications of spinals and epidurals.

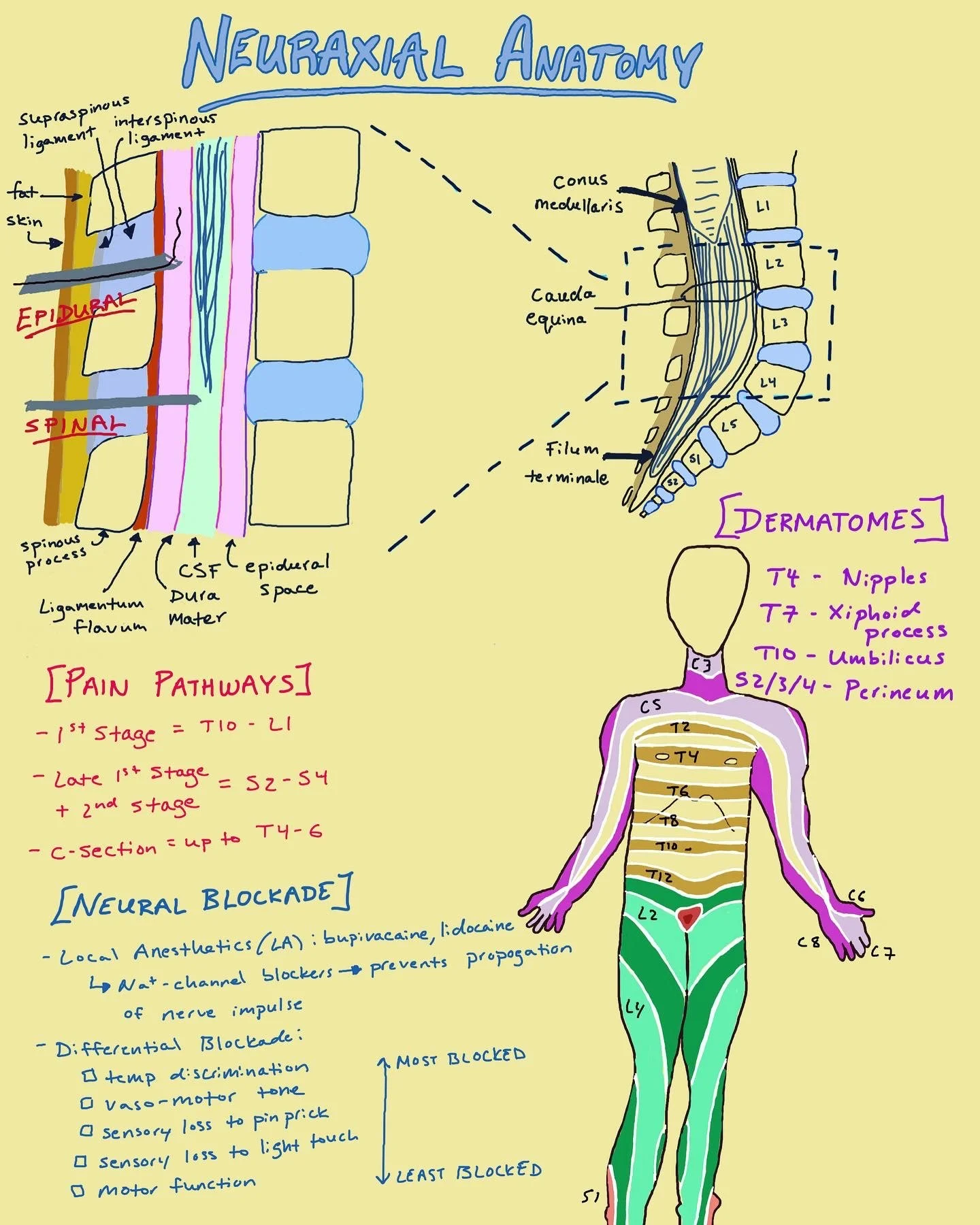

To start our discussion of neuraxial anesthesia, let’s talk about anatomy. One of the hardest things about neuraxial technique is that your procedure is done blind and you rely heavily on landmarks and your understanding of the patient’s anatomy.

Ultimately our goal is to get into the epidural space or the subarachnoid space to deposit local anesthetic to block pain sensation during labor or a c-section. You will be aiming for the lumbar space. Palpating the posterior-superior iliac crest of the patient hip will usually be inline with the L3-L4 space. Next, the spinous process will tell you where the patient’s midline is.

After you puncture the skin and fat, you will feel your needle engage with the first ligaments of the spine - the supraspineous and interspinous ligament. The next ligament you will reach is known as the ligamentum flavum - noticeably “tougher” than the previous ligaments. Next, you will find yourself in the epidural space. This is where you would stop your epidural needle and pass a catheter through the needle. If you were doing a combine spinal-epidural (CSE), you would pass a spinal needle through the epidural needle, into dural sac, and inject medicine, before passing the epidural catheter. For a typical spinal, you pass through the epidural space, puncturing the dural sac.

Knowing dermatomes will help you know if your epidural or spinal is working at a good level before labor and surgery. Landmarks to remember for dermatomes are T4 (nipple line), T7 (xiphoid process), T10 (umbilicus or belly button), and S2/3/4 (perineum).

During the 1st stage of labor, pain pathways originate from the T10-L1 spinal level. During late stage 1 and stage 2, pain originates from S2-S4. For cesarean sections, a block up to T4-T6 is usually needed for the visceral sensation.

Lastly, local anesthetics work by block sodium channels, which conduct electrical impulses down nerve fibers. Once the nerves are blocked, a “differential blockade” occurs. The losses experienced by the patient from most blocked to least blocked are temperature discrimination, vasomotor tone, sensory loss to pinprick, sensory loss to light touch, and motor function.

Besides the anatomical differences between a spinal and epidural, there is a difference between how you dose both options.

After placing an epidural, give a test dose to rule out an intrathecal injection or intravascular injection. This is accomplished by injecting a mixture of local anesthetic and epinephrine. If the patient does not experience immediate lower extremity weakness or a heart rate increase of at least 20 to 30 bpm within 30 seconds, you have effectively ruled out both intrathecal or intravascular injection.

Following your test dose, you will bolus an epidural with about 5 to 10ml of 0.125-0.25% Bupivacaine or Ropivacaine. This allows the nerve block to build up to an appropriate level of analgesia over the course of 15 minutes. After the bolus, a continuous infusion of 0.0625% Bupivacaine or 0.1 % Ropivacaine will start at a rate of 8-12ml/hr. If you set up a patient-controlled epidural analgesic (PCEA), a typical setting would be an 8ml demand bolus with a lockout time of 10 minutes on top of an 8 to 12ml/hr basal infusion.

Because C-sections require a higher dermatomal level of analgesia, patient’s with an epidural will need a “top-up”. This is bolus of around 15-25ml of local anesthetic such as 3% 2-Choloprocaine, 0.5% Bupivacaine, 2% Lidocaine with the addition of epinephrine for faster onset of action and less vascular uptake from the epidural space.

The dosing of spinals is based on the volume of CSF in the patient’s dural sac. The best surrogate for this is a patient’s height. Hyperbaric bupivacaine contains dextrose that causes the medication to sink when injected, creating a greater block on the spinal levels below your injection site. Isobaric bupivacaine doesn’t contain dextrose and typically stays around the level of the injection.

Opiates can be added to local anesthetics for spinals and epidurals to create a “denser” block without any motor effects. However, these opiates still contain the same side effects as systemic opiates because they are taken up by the blood stream. Morphine is a hydrophilic opiate and has a longer duration of action. Fentanyl is a lipophilic opiate and only lasts about 2 to 4 hours.

It is always important to know what complications to look out for after performing any procedure. For spinals and epidurals, there are a few important ones to look out for.

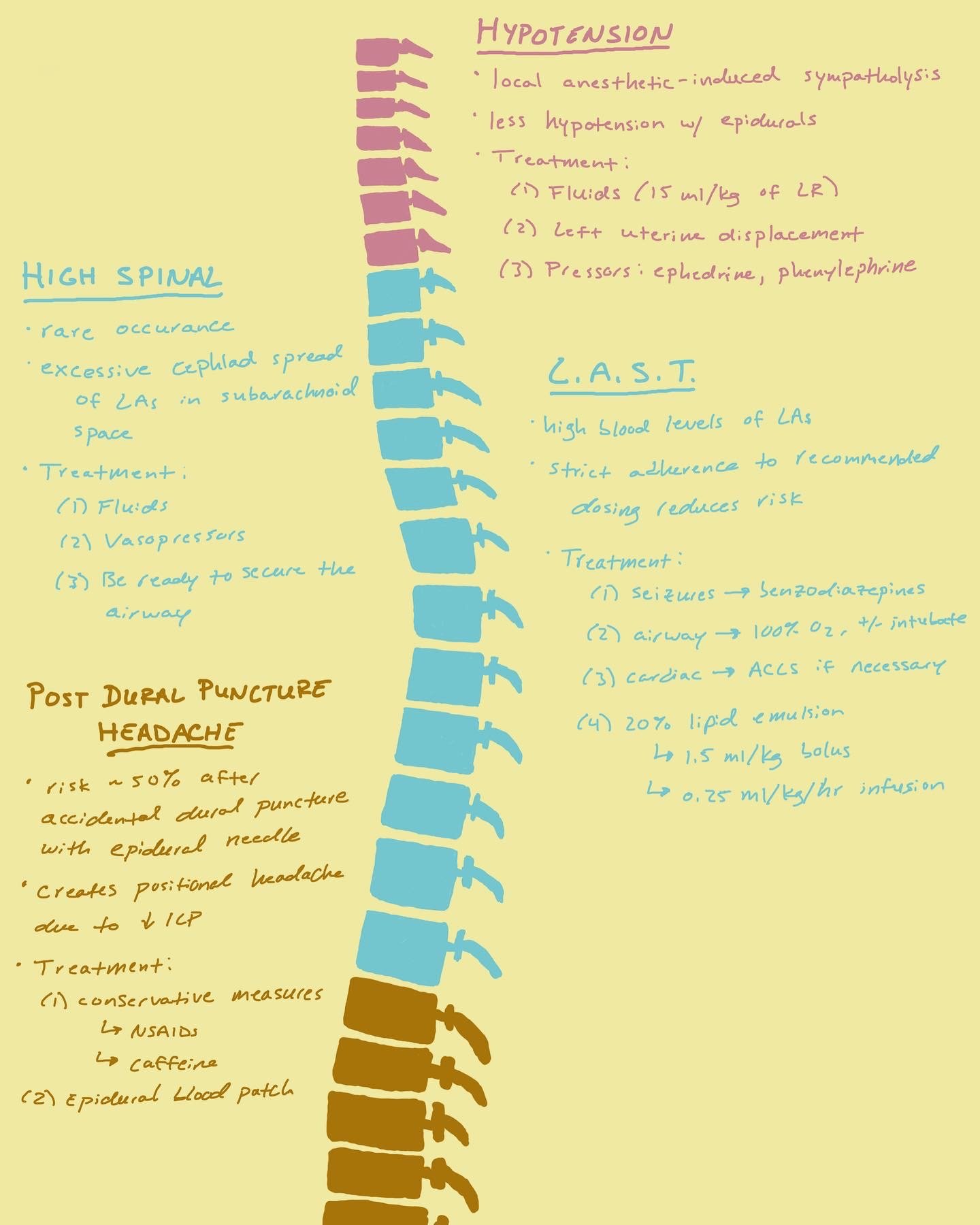

The most common complication to occur after a neuraxial anesthetic is hypotension. This is caused by the blocking the sympathetic nervous system, which lives primarily in the thoracic level of the spine. Once these nerve fibers are blocked by the local anesthetic in your neuraxial injection, there is a decrease in norepinephrine and epinephrine which then causes a dramatic drop in preload and afterload. The best way to prevent or treat this drop in blood pressure is with IV fluids, vasopressors such as phenylephrine and ephedrine, and positional changes to reduce aortocaval compression.

Another commonly seen complication is a post dural puncture headache. This is a positional headache that is most intense when the patient stands. It is caused by a leakage of cerebral spinal fluid (CSF) after the dura has been poked by a needle. This is turn causes a drop in the intracranial pressure. The incidence of this has reduced in spinal anesthesia since the development smaller gauge needles with pencil-point tips. However, when an epidural needle punctures the dura, the rate of PDPH can be as high as 50% due to the diameter size of the epidural needle. The treatment for this can be divided into 2 categories: conservative vs invasive. Conservative treatment would include rest, over-the-counter NSAIDs/Tylenol, and caffeine. PDPH can resolve over the course of 1 to 3 days. However, if patient’s have prolonged or intense symptoms, invasive treatment would involve an epidural blood patch. This involves sterilely drawing blood from a vein, then injecting the blood into the epidural space to apply pressure against the dural defect to close off the leak.

There are two other rare complications that are real medical emergencies and require prompt recognition and action. The first is a high spinal. This happens when there is an accidental injection of an epidural dose of local anesthetic into the subarachnoid space. This is usually caught by the test dose. However, if the patient starts experiencing arm weakness or difficulty breathing, you should be prepared to treat profound cardiac and respiratory failure with fluids, pressors, and securing the airway.

And lastly, you can have LAST - or Local Anesthetic Systemic Toxicity. This is a result of high blood levels of local anesthetic which then can cause neurologic and cardiopulmonary issues. Initial treatment for LAST usually can involve benzodiazepines for seizures, pressors for hypotension, and intubation to secure the airway. The definite treatment will be 20% lipid emulsion which pulls the local anesthetic from circulation, reducing its toxic effects.